February is Black History Month, and it has been since 1976 when President Gerald Ford officially recognized it.

Black History Month has drawn negative attention for only taking into account Black achievements one month out of the year, when celebrations of Black history should permeate the teaching of American history year-round.

Carter Woodson, the man viewed as the founder of Black History Month, hoped for his creation to one day become obsolete. However, we’re not there yet. Work still needs to be done to ensure that the history we teach truly and fairly reflects us all.

It is important to look at the past to help us remember the sacrifices of those who paved the way. The past, no matter how tumultuous, must be recognized.

Rondo Neighborhood

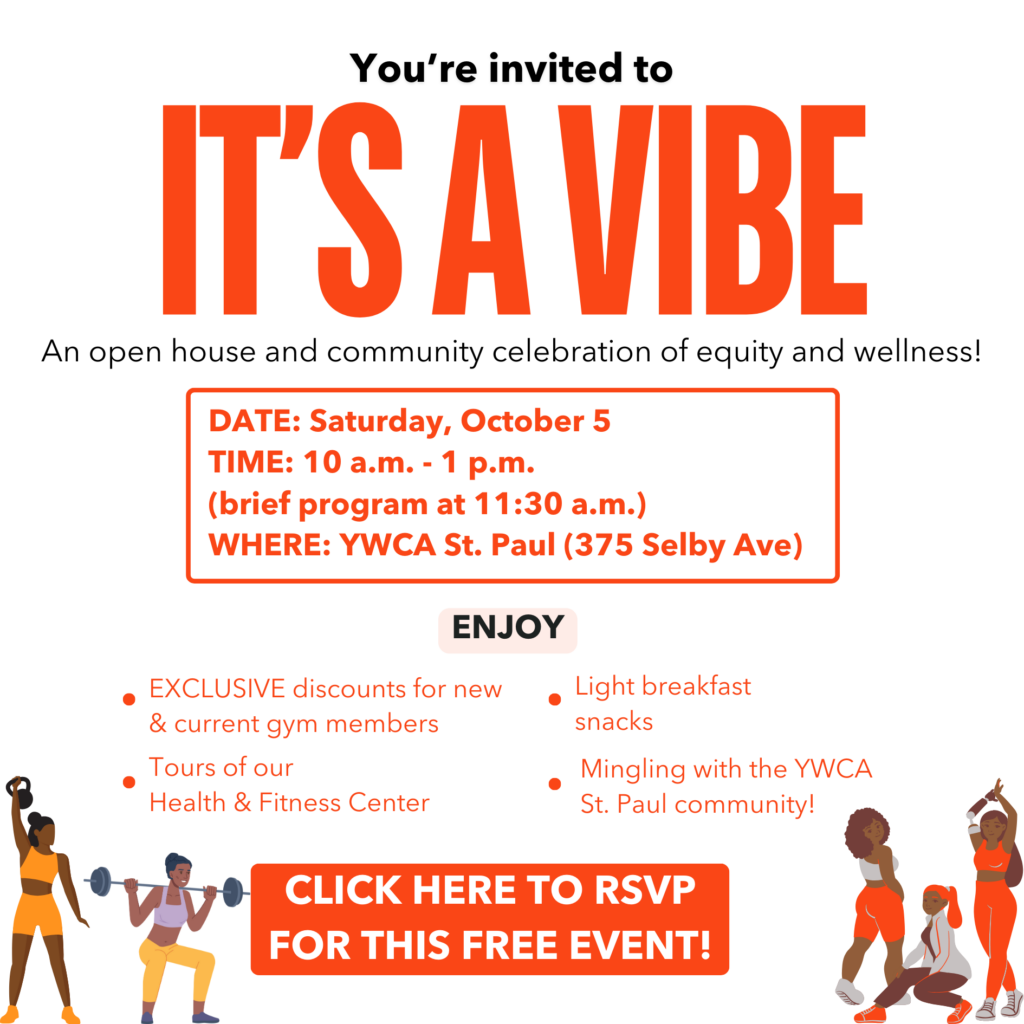

Today we look at the Rondo neighborhood (roughly between University Avenue to the north, Selby Avenue to the south, Rice Street to the east, and Lexington Avenue to the west), where YWCA St. Paul is located and creates a strong sense of community. St. Paul’s Rondo neighborhood was the center of the Black community in the Twin Cities for much of the 20th century.

From the beginning, Rondo was a haven for people of color and immigrants. Its namesake, Joseph Rondeau, moved there in the late 1850s from a location close to Fort Snelling where he had faced discrimination due to his wife’s mixed white and indigenous heritage. French Canadian immigrants followed Rondeau to the area in the late nineteenth century; later, German, Russian, Irish, and Jewish families found homes there.

The Rondo neighborhood, once home to 80 percent of St. Paul’s Black residents, consisted of a working-class community, supported by social clubs, religious organizations, community centers and a thriving business community. It was home to doctors and lawyers, barbers and maids, civil rights leaders and Pullman porters.

Destruction of Rondo

The Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956 provided funding for cities to create a network of freeways across the country. So, the state of Minnesota decided to build a 13-mile connection between downtown Minneapolis and St. Paul. A proposed northern route, along abandoned railroad tracks near Pierce Butler Road, would have been less disruptive to neighborhoods, but a more central route, right through the heart of Rondo, was chosen.

Rondo residents didn’t have pockets deep enough to alter or reroute the project — something predominantly white neighborhoods would at least partly achieve years later.

Rondo was devastated in the 1960’s to construct Interstate-94, which cut the neighborhood in half, causing the loss of 700 homes, around 300 mostly Black-owned businesses and a significant drop in population and homeownership in the area. Hundreds of millions of dollars of community wealth was lost.

Many families didn’t receive fair market value for their homes, and because of discriminatory housing practices like redlining and restrictive covenants, they had limited choices of where they could move.

Rondo Today

While the construction of I-94 radically changed the landscape of the neighborhood, the community of Rondo still exists, and its persistence and growth are celebrated through events like Rondo Days in July and the Selby Avenue Jazz Festival.

In 2016 a formal apology was given formally by Minnesota Department of Transportation Commissioner Charlie Zelle and then St. Paul Mayor Chris Coleman. The Rondo Commemorative Plaza was then installed in to commemorate the Rondo community.

Recently, a group called Reconnect Rondo has a plan to right a wrong and make up for some of the racial injustices of the past.

Their plan calls for a cap over a portion of I-94 and build a land bridge several blocks-long with affordable housing, green space, a museum and a marketplace that would re-link both sides of the neighborhood cut in half by the freeway and restore a community destroyed 60 years ago.

To learn more, here are some additional resources:

St. Paul’s Past: Rondo, St. Paul’s African-American Community (video)

Jim Crow of the North (video)